Here's the latest installment in our series of articles dedicated to the race for volume, and its consequences on music, sound and human ears.

The day came when our dear record industry friends (who, let it be said, are nothing but salesmen for whom the artistic value of a work is a variable measured in terms of profits) decided to take their back catalog and release remastered versions. In other words, versions whose overall volume is artificially increased, with a complete disregard for the music’s dynamics and the (often) exceptional work of the mixing engineers, not to mention the musicians themselves.

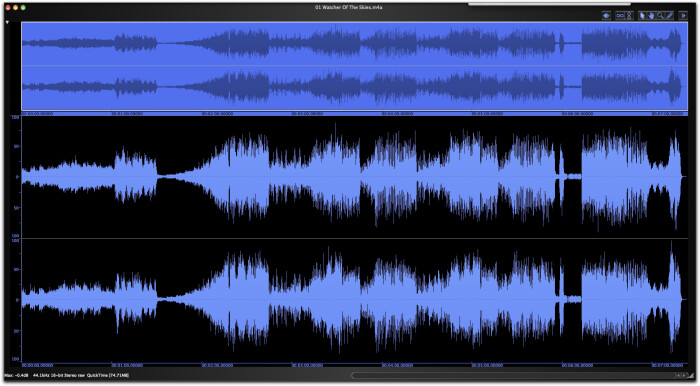

In the screenshot below you can see the original CD release (1985) of a classic Genesis song, “Watcher of The Skies”, taken from the Foxtrot album (Charisma, 1972; vinyl release). This song’s dynamic range is 14dB, while the album’s is 12dB on average.

If you examine the waveform, you’ll see two outstanding peaks, one right before the middle of the song and the other one almost at the end. These two peaks could’ve been “limited” back in the day or reduced during mixdown in order to achieve a higher output volume. But they weren’t. The mix was considered done and, if you wanted to listen to the song louder, you only had to pump up the volume on your listening system.

Remember that back then, people used VU-meters (with a response time of 300ms, so peaks weren’t displayed with precision) or peakmeters (with a response time of 10ms, which meant they displayed peak averages), and there were no digital audio editors.

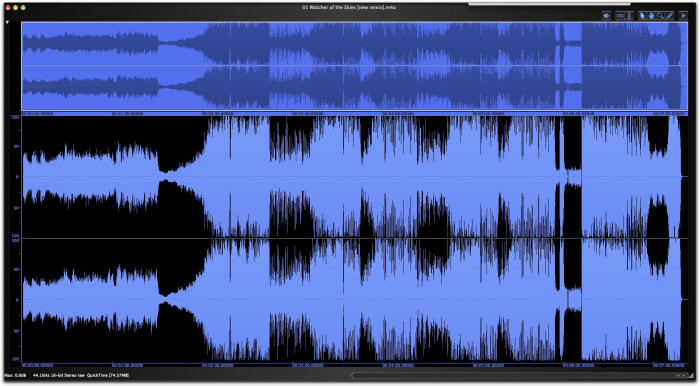

Let’s take a look now at the “remastered” version, dating from 2007

.

The album’s overall dynamic range is 10dB, while the song’s is 8dB, besides being loaded with intersampled clipping. Where the first waveform showed the dynamic subtleties of the musicians’ performances and the production, it’s easy to realize that the nice crescendo starting at 1:30 has been shattered. Not to mention the crushing of the rest of the parts of the song. Another phenomenon commonly associated with overcompression (in addition to the overall altering of the timbre) is the exaggeration of almost all frequencies. Especially when overcompressing with a multiband compressor (a great tool, which is also unfortunately responsible for sonic butcheries).

Let’s now take a look at the volume achieved by the individual frequencies across the entire song (maximums in red and averages in yellow). The images speak for themselves.

Add to this the grinding resulting from current radio broadcasting practices and you end up with a nice and flat-looking log. Granted, not many radio stations play 1972 Genesis anymore…

But still, all music is being sacrificed in the name of this crazy race for the loudest-sounding track.

How to describe those who engage in this type of practice? And, for the sake of coherence, don’t blame only the salesmen: Technicians, engineers and all other people involved in the mechanics of it are just as responsible. Without them there wouldn’t be any sonic massacres. And, sorry, the “if I don’t do it someone else will” philosophy is not good enough for me. I’m sick and tired of people eluding their responsibility.

What is mastering, anyway?

That’s a great question that conjures different answers. For those of you who still have a vinyl collection from before the mid '80s, take a look at the sleeves and, in most cases, you’ll be able to find straight away who engineered, produced and mixed the album, but you’ll have a hard time finding out anything about any mastering.

Because, even if the principle behind mastering ─ namely preparing and adjusting multiple tracks to a given media, which is something we’ll talk about in the next article ─ has been around for lots of years, its systematization, especially regarding artistic creation, became widespread only with the arrival of the CD and digital formats.

“If you have a problem with the recording, solve it at the recording stage; and if you have a problem with the mix, solve it during mixdown.” This principle ought to be applied systematically. It’s not wise to assume that the problems from one stage can be readily solved in the next one. And yet, that’s the way we tend to do things these days, pretending that we can do more (with less) at the mastering stage than we can at mixdown.

To paraphrase one of the most respected voices in the field — Bob Katz (see “Mastering Audio, The Art And The Science” by Bob Katz, Focal Press, 2002): Mastering engineers listen to your work in an objective and experienced way. They are used to technical and aesthetic mistakes. Sometimes they don’t do anything…at all! If they sign off on a track, it means it’s ready go.

The rules have certainly changed with the the arrival of digital audio, together with home and project studios, as well as the mixing in places not fit to the task (the consequences of mixing in a room that isn’t acoustically treated or whose defects haven’t been taken into consideration can be heard right away). In this scenario, the intervention of an extra pair of ears, the implementation of an additional processing stage, and the views of a person unrelated to the project, can prove very useful, even indispensable.

But many mastering engineers have forgotten that when a mix is well-balanced there’s no need to add, remove or do anything else to it. Nobody can do a better job at mixing a song than an experienced mixing engineer, in an adequate room in front of a multitrack recorder, be it analog or digital. It’s a simple matter of logic. Who do you think can deal better with all sound-related issues that may arise (volume, EQ, compression, spatialization), someone working with individual tracks (48 tracks, for instance) or someone working with a stereo mix or a couple of stems (the famous Gang of Four approach)?