In this new installment we'll continue discussing the consequences of volume on music, sound and human ears.

By now you have probably started to understand the consequences of the loudness war on recorded music, music broadcasting, mobile listening, and your ears. But you shouldn’t forget live events. As of today it is nearly impossible to go to a concert without the need of earplugs. What a crazy paradox: Needing to wear earplugs in order to listen to and enjoy music!

Few countries have legislative measures specifically aimed at recreational noise exposure. In France there’s currently a regulation that limits the level in concerts and discotheques to 105 dBA. Peak level? No, mean volume! And 120 dBA peak level. If you consider the regulations for working environments, a concert at this level, without any hearing protection, shouldn’t last for more than 20 minutes! It’s hard to make any sense of it ─ are lawmakers even aware of such incoherences? How is it that something that applies to a working environments (and rightly so) does not apply to concerts?

It is, however, a matter of setting new limits, imposing lower SPL ranges that are safer for the patrons.

Besides concerts and clubs, think about events such as raves and EDM festivals, where volume levels are staggering and the regulation of them virtually nonexistent.

Everywhere, all the time

And what about movie theaters? Well, it’s pretty much the same. And I’m not talking about noise pollution in the cinema itself (popcorn, cellphones, the guy who narrates the film to his girlfriend, etc.). But rather about the volume of certain films.

Consider these two factors: The mix of blockbusters (big Hollywood action films, as well as some other movies that don’t fit in this description) and the volume inside the movie theater itself. If you’ve watched The Bourne Supremacy, Star Wars: The Clone Wars, Inception, The Avengers, or Gravity in a film theater, you probably know what I’m talking about.

In this type of films there’s sound everywhere. Right from the first frame to the last one there is music, ambience, special effects, and dialog. The result? A soundtrack that is overcompressed in order to get everything in the movie, in an era when Dolby and DTS systems provide incredible dynamics.

The second problem adds up to the first one: Contrary to what most people think, there are no limits in film theaters. You don’t have to be too bright to realize what two hours in a cinema can do to your hearing, now do you?

The issue of loudness in movie theaters is pressing enough to have caused the Audio Engineering Soceity convened a special committee to look into and report on the issue. In France, the Association of Audiovisual Professionals (Commission Supérieure Technique De L’Image Et Du Son) has only recently taken the matter into its own hands, for instance. In a statement from 2011 it stated the following:

“[…] with the arrival of digital audio, we are more often faced with encodings to absurd levels […]. It is imperative that all professionals involved in the different stages in the audio chain of a cinema work together so that audio levels in film theaters do not become a problem of public health. One of our main priorities in terms of technical recommendations is to reduce the sound pressure level in movie theaters to 79dB […]”

Hopefully a solution will be found soon. But the problem doesn’t just stop there, the all-digital era has also brought with itself new practices in movie theaters: The need for fewer technicians (sometimes only one in an entire multiplex), films encoded, protected (RSA and AES) and stored in distribution servers, with almost paranoid levels of security precautions. The tasks of the modern projectionist are almost limited to receiving the disk on which the movie is stored, copying or adding it to the server, and entering the separately provided authorization key, which allows the projection of the film for a limited time and on a single server.

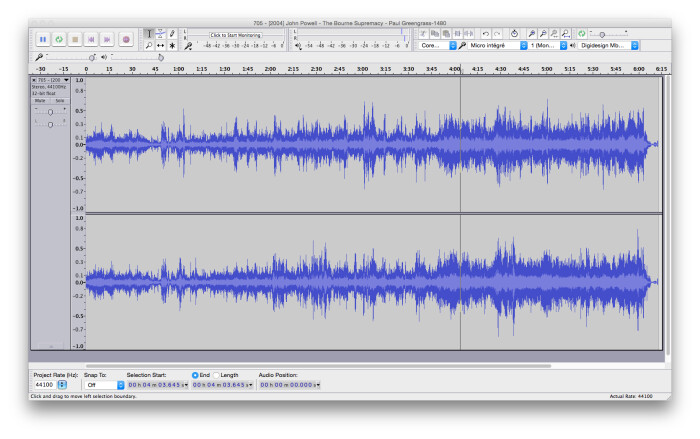

But let’s go back to The Bourne Supremacy. Here’s a screenshot of the audio: 13 dB of dynamic range, during a scene where the softest noise (the spit, the throwing of the walkie-talkie on the seat, the unfolding of the map) is almost as loud as the engine of a car or the music, which, as a result, doesn’t transmit anything. The effect can be devastating in a movie theater if the volume is too loud (which is often the case).

These scenes would be much more understandable and bearable if some provisions had been taken, instead of trying to cram everything in. It’s the exact same problem as with music.

A counterexample: If you’ve seen Peter Yates’ Bullit and the mythical chase scene (the mother of all chases to come, including the recent Drive by Nicolas Winding Refn), do you remember the music and the noises (from the hubcaps, other cars, the tram, the city) during the scene? You can watch it here.

Initiatives and Results

As I mentioned before, some new attempts and initiatives are trying to tackle the issue. One of the first attempts aimed at the general public was the integration of Sound Check into iTunes, Apple’s playback and sync software for all sorts of iDevices. This feature can accessed via the Preferences menu.

Even more interesting is the fact that Sound Check has become the default setting and it can’t be deactivated in iTunes Radio, Apple’s radio streaming service. What it does is automatically adjust the audio level. But it’s goal is not to increase the level but rather to allow you to hear all songs at approximately the same volume, avoiding big differences between songs or from one station to the other. Like with every such processing, the songs that will sound better are those that have a bigger dynamic range, since the attack and peaks are preserved. Songs that are “flat” will see their overall level drop drastically and their lack of dynamics and attacks will become obvious, even if the loudness is the same. We can only hope that this outright exposure of overcompression will make professionals turn again to producing sound without the need to destroy it and its dynamics (you might want to read Bob Katz on the topic).

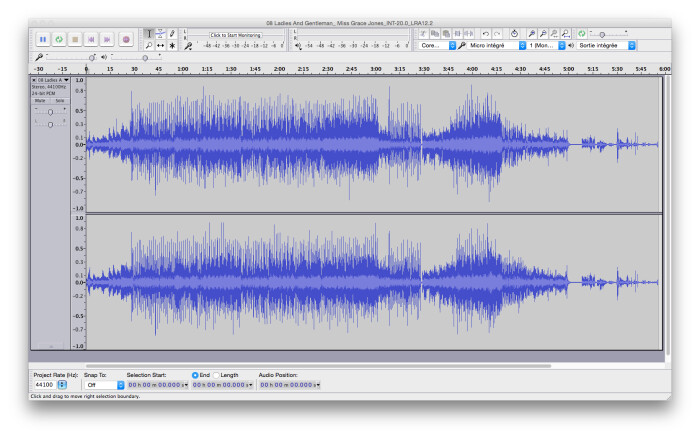

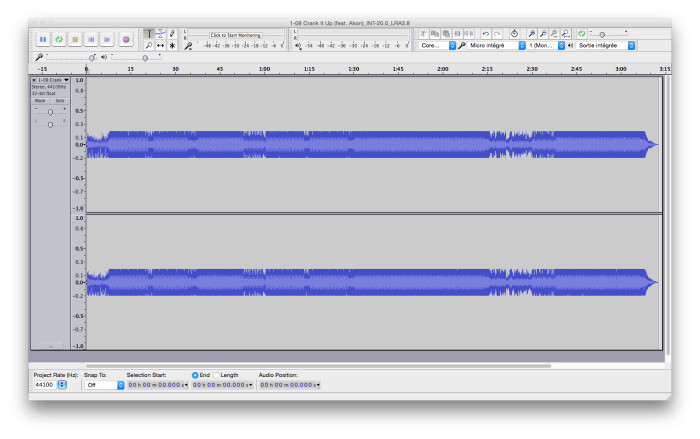

Here you have two screenshots to illustrate my point: Grace Jones and David Guetta’s songs I referred to in previous articles after processing them to get the same perceived volume (in the next article I’ll explain what standards and processing I applied to them).

In the end, one has a clear, dynamic sound with lots of details, while the other one remains…well, flat.

- 01 GraceJones 00:32

- 02 DavidGuetta 00:17