In the previous article I introduced you to some of the most popular cadences and chord progressions. But there are still some left!

The return of the circle of fifths and the neighbor tones

Let’s start by recalling the circle of fifths and the neighbor tones I mentioned in article 3, which you should quickly reread to better understand what’s coming.

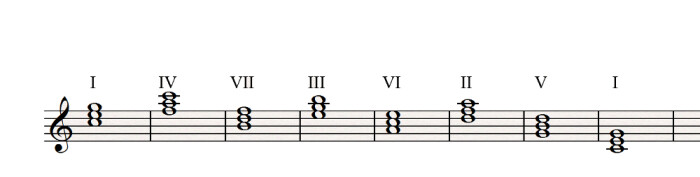

In the following example the progression follows the key order defined by the circle of fifths (with the chords in root position):

I – IV – VII dim – III min – VI min – II min – V – I

And here’s a quick reminder on neighbor tones:

-

VI (the scale’s relative)

-

IV (the scale’s subdominant)

-

V (the scale’s dominant)

-

II (the relative to the IV degree)

-

III (the relative to the V degree)

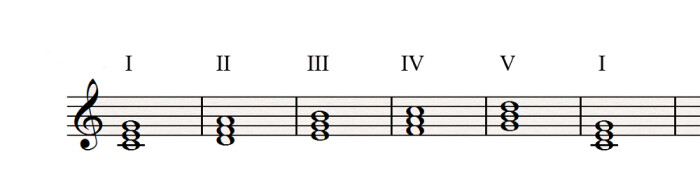

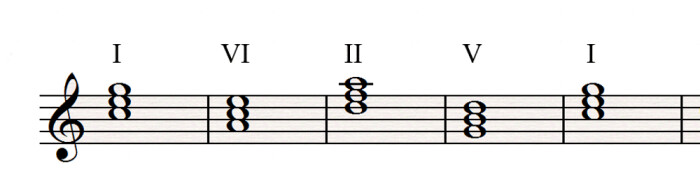

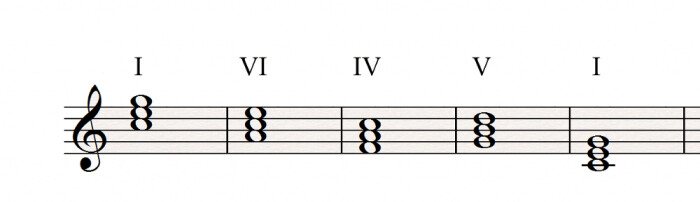

In article 3 I told you neighbor tones can be used quite freely to create workable progressions. Here are some examples, always in root position (we’ll talk about inversions below):

I – II min – III min – IV – V – I

I – VI min – II min – V – I (remember rhythm changes?)

I – VI min – IV – V – I

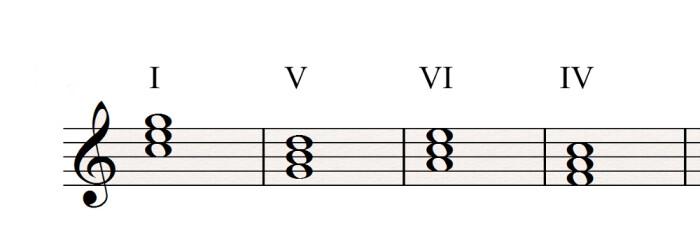

I – V – VI min – IV

Magical progressions

The last progression is one of the so-called “magical” progressions, very commonly used in pop music, as the next video can attest:

And in case you are wondering if this only applies to music in English, think twice. The French version, for instance, goes something like this:

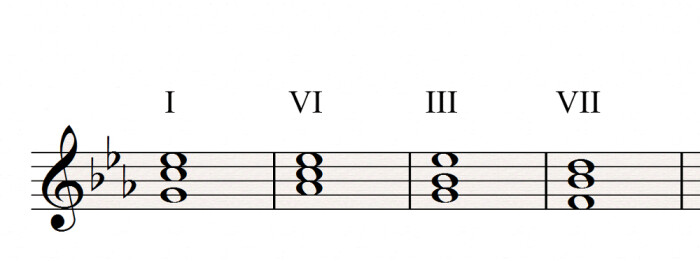

I min – VI – III – bVII

As exemplified in this video (in French):

There are a couple of things to point out regarding the last example. First, the scale used is natural A minor, so the seventh degree is not based on the leading-tone (½ tone below the tonic), but rather on the subtonic (one whole tone below the tonic).

The return of inversions

Secondly, you might have noticed that I used an inversion of the chords (refer to article 4), which allows me to vary the highest note only very slightly to reinforce the overall coherence and pull off a nice bass line. Another example of how to use inversions to get a bass line working would be a diatonic descent, like this:

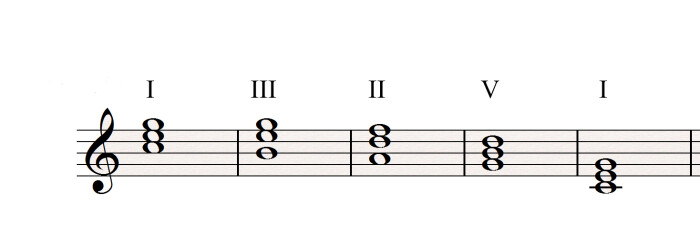

I – III min (inversion) – II (inversion) – V – I

In the sound clip below, the bass of each chord is played first, so you can hear its movement better.

To finish, you might have probably noticed that all the progressions I talked about in the last couple of articles follow the “attraction” scheme I told you about in article 11. You see how everything just seems to fit together nicely?

In the next article we’ll see how certain chords can be replaced by some others, in other words chord substitutions.