Top mix engineers will tell you that they instinctively know when they're finished with a mix. But for those of us who haven’t reached that level yet, it’s usually hard to have that kind of certainty. Here are some questions to ask yourself to help you determine if your mix is ready for prime time.

Does each element have its own space?

The key to a good mix is making sure that every element can be heard distinctly. Panning is one variable that can help separate elements, but it’s not the only one. EQing, especially by cutting frequencies, can allow you to carve out space for an instrument or vocal that’s otherwise obscured by another element in the same frequency range (see our article on frequency masking). For instance, if guitar and piano chords are in the same frequency range and muddying each other up, consider inserting a high-pass filter on the guitar to roll off everything below about 150 Hz or even 175 Hz, so that the piano chords have some space to pop through. (Read our story on high-pass filtering for details on how to use that technique.)

Another way to carve out space is by moving elements back and forth in the soundscape with ambience. For example, a vocal with a short reverb will feel more up front and “in your face, ” compared to one with a long-decaying reverb.

The combination of all three of those variables, panning, ambience, and frequency can help you craft a mix where each element can be heard.

Are the dynamics evened out?

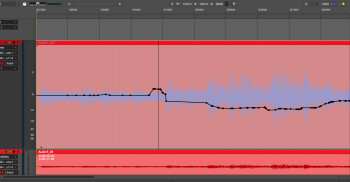

Nothing screams “amateur” in a mix more than when a vocal or an instrumental pops way up in volume. Although you certainly don’t want to squeeze all the dynamics out of your mix, you want to make sure that nothing will make the listener reach for the volume control to turn it down. Conversely, you don’t want lines or words of a vocal or instrument track to be unintelligible due to volume drops. Probably your best weapon for evening out the dynamics is volume automation. Find those spots where it’s too loud or too quiet and draw in automation (or use your onscreen fader in “touch” mode to compensate. For more on automation modes, check out this article.) Once things are in the ballpark, compression will help smooth the track out further.

Pay careful attention that lead vocals and solo instruments are at the level you want vis-a-vis the rest of the mix. It’s easy to make those elements too loud as a whole. Some musical styles feature louder vocals than others, but generally speaking, your goal is to make the vocals sit nicely in the mix and not too far on top of it. Before getting into the automation of small parts, get the general level of vocals and instrument lines or solos where you want, and then automate the peaks and drops.

Have I overdone it with the processing?

Since a mix unfolds over a course of a number of hours or days, it’s easy to be gradually adding processing — a little here and a little there — as you go along, and before you realize it, you’ve drowned the song in reverb or delay, or squashed it with compression. So when you think your mix is in a close to finished state, take a step back and think, “Do I really need all of this?”

Often, by backing off a little on an effect you can create a stronger end product — especially with reverb and delay. Of course, it depends what you’re going for. But if you want a more contemporary sound, dial back the reverb a bit if it’s sounding a little cavernous.

Also be careful not to over compress. Does everything seem too squashed? Do transients seem a little flabby. Maybe time to back off a little.

Of course, if you’re saving incrementally (see the section on incremental saving in this article), so you can always revert if you later decide that maybe you had it right the first time.

Will the mix translate?

It’s important to figure out whether or not a mix will sound good once its listened to outside of your studio. This is especially important if your studio doesn’t have acoustic treatment, and could be giving you a distorted sonic perspective, which can cause you to over- or under-compensate, especially when it comes to EQ. The area where this seems to be the most problematic is the bass end of the frequency range.

Here are a few suggestions for helping make sure your mix will translate to other systems. If you have more than one set of monitors, switch between them frequently. While this won’t defeat acoustical gremlins in your studio, it will give you some added perspective. Try turning around and listening to the mix coming from behind you, walking to another part of the room, or even listening from outside the door — just to change up the way in which you’re hearing things.

It’s really helpful to listen on other systems in other locations. Your car is the classic one, because you’re used to listening to music in it, and will know if your mix sounds unbalanced if you hear it there. But also try listening on other systems: on earbuds, on a boombox, etc. I know of a couple of world-class mix engineers who rely on boomboxes as “real life” mix references — and they’re working in acoustically treated rooms on the best monitors. In any case, a good mix will sound good on any system, so if you like what you hear it in multiple places, you’ve probably done a good job.

Another way of checking is by A/B referencing (see our article on the subject) it against commercially released recordings. By switching back and forth between your mix and the reference recording (its crucial to have the volume balanced between them), you can see how your work holds up. If something is glaringly different, for example the bass and kick drum levels or the vocal-to-instrument balance, you’re likely to notice.

Listen at different levels. Your mix should sound good whether it’s loud or soft. Sure, it’s going to sound more dramatic at louder volumes (unless it’s a ballad), but it should still sound balanced when you listen a lot more quietly. If not, you probably need to work on it more.

Check your mix in mono. If there are phase issues (see our article), you will hear them right away when you hit that mono switch. If things turn into a mess in mono, it’s best to back track and check your stereo sources to see where the problem is. If you have stereo sources recorded on separate mics, try flipping the phase on one of them and see if that helps.

Have I lost my perspective?

At the end of a long mix session, the answer is probably, “yes.” We all have a tendency to “lose our ears” after a few hours of mixing. Our perspective is gone and we start making bad decisions. You can slow down the onset of that by taking frequent breaks, and not monitoring too loud. Turn it up briefly if you want to hear what it sounds like really loud, but then bring it back to a comfortable level.

It’s always wise to let your mix sit overnight or for a day or two, and then check it — even if you think you’ve totally nailed it — unless you’re on a strict deadline to finish. When you reopen it, you’ll probably notice things that need tweaking.